When Summer Thomas found out that her son, Kaius, got into Campbell STEM Elementary through the district’s lottery, she was thrilled. They’d gone on a tour with the school’s principal and watched as kids engaged in dinosaur-themed activities.

“I really did feel like I won the lottery when I saw that he had gotten in,” she said. “It felt amazing because I really believed in the direction that Campbell STEM was going in. But then reality started setting in.”

Thomas opened up Google Maps and realized the commute would add an hour of driving to her day. Plus, there wasn’t an after-school program where Kaius could stay until she picked him up after work. So they had to decline.

“I just started realizing that I don’t think I could wake up an hour earlier and wake my son up an hour earlier and spend all that extra money on gas,” she said.

Now, Kaius attends Klatt Elementary School. It’s in their neighborhood — Kaius can even walk to school — but after-school care is still a challenge. The local nonprofit Camp Fire previously ran an after-school program at Klatt before the pandemic, but now only has programs at a dozen Anchorage schools.

Starting this Friday, Anchorage parents will learn if they won the district lottery that allows students to enroll in a language immersion program, optional program, charter school or a neighborhood school outside their area. Superintendent Deena Bishop said one of the school board’s goals for next year is to make sure families from underrepresented groups know about it.

“It’s really to engage and make the pool of people in the lottery larger and representative of the school district so that the chance of getting selected in the lottery is greater,” she said at a work session last month.

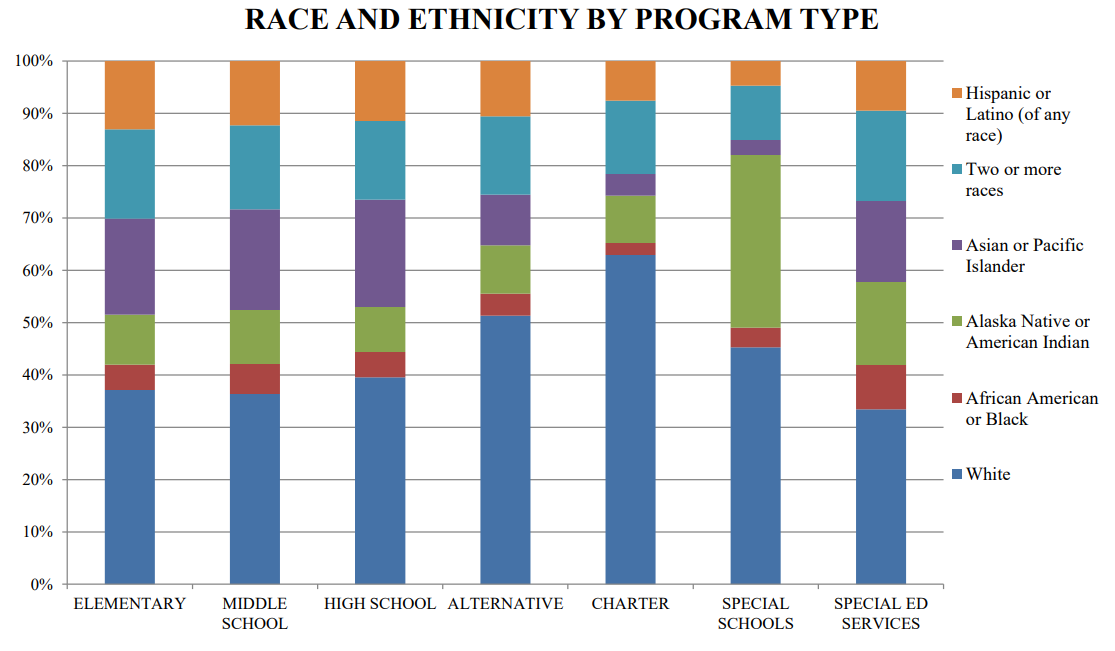

Sixty percent of students in the district identify as non-white, while non-white students make up only 37% of charter schools.

That’s the data on enrolled students. But the district doesn’t know the racial makeup of the lottery pool.

This year, the district included an optional question on its lottery application page asking for the applicants’ race and ethnicity. Dan Barker, the district’s director of elementary education, said this will help the district understand at what point in the process they’re losing families of color.

“At this point, many of our choice programs have been in place for well over 20 years,” he said. “We literally don’t know if folks are self-selecting not to apply because they’re already aware of some of the obstacles that would be in place in participating in some of those programs, or if there are other reasons that they’re not interested in applying.”

Barker said it’s too early to say what changes the district might make once they get the results later this summer. But one might be simply raising awareness that the choice programs exist.

Diane Hirshberg researches education policy at the University of Alaska Anchorage Institute of Social and Economic Research. She said there’s an “experience gap” between parents who attended charter or optional schools themselves and those who didn’t.

“It’s not that these parents don’t care about education — they care very deeply about education,” she said. “But it is simply that there are expectations, such as enrolling online for parents who may not have a computer in the home, or may not understand what the choices are and make an informed choice when this has not necessarily been something they’ve been engaged in in the past.”

A major expectation is that parents can provide transportation themselves.

Over the years, Barker said, charter schools haven’t been required to provide transportation, lunch, after-school care or other programs that could make them more accessible to a wider range of families. Instead, parents and other groups seeking to create new charter and optional programs have been told to focus on staying “budget-neutral,” he said.

“You fast-forward that over a long time, and that provided a different level of access, because the system wasn’t providing the same resources to all programs,” Barker said. “I think that’s a very appropriate conversation for us to have as a community. Where it’ll end up, I guess, is anybody’s guess. But everybody should be involved in the conversation, which is really what this is about for me.”

Representatives from charter and optional programs set up tables at the district’s Education Center and answered questions at an informational event last month. Brandon Locke, the district’s director of world languages and immersion programs, said if a family can’t arrange transportation to get their child to the school of their choice, there’s likely a different program nearby that would be a good fit, too.

“If you take a look at our programs, they are all over the city,” Locke said. “So really, there is something for everybody, even outside of the traditional neighborhood school.”

Fadwa Edais did just that. She’s bilingual — she speaks Arabic and English — and she wanted her kids to get the benefit of speaking multiple languages, too.

“My family lives in Los Angeles, my husband’s family lives in Texas, and both of their second languages are Spanish,” she said.

She looked at the district’s Spanish immersion programs and found Government Hill Elementary. But the family lived more than 10 miles away. During rush hour, that drive could take up to 45 minutes.

“And where’s the family time?” she asked. “You’re spending an hour and a half every day just on the road. Everything is fast, fast, fast. Let’s go, let’s go, let’s go. Honestly, it’s not my culture, and I don’t believe in that.”

Plus, Edais and her husband both work, so they’d need to pay extra money for daycare before and after school. Instead, they enrolled in the Japanese immersion program at Sand Lake Elementary, their neighborhood school. She’s happy with the program, but it wasn’t her first choice.

One optional program that does provide transportation is King Tech High School. Students can take the bus to their neighborhood high school and then get picked up by another bus to go to King Tech. Nearly 850 students attend King Tech, either for a full day or a half day, and half of the full-time students are economically disadvantaged, according to the school’s online profile.

On average, the district spent more than $57,000 on King Tech’s student travel in 2018, 2019 and 2020. In a district already facing a budget deficit, replicating that kind of transportation system for every optional program would come at a significant cost, Barker said.

For now, he hopes this year’s data will help them understand whether they need to increase outreach, address barriers like transportation and after-school programs, or both.

“Leveling that field is an absolutely critical component for us, as a community service program,” Barker said. “Everyone in our community has a stake in our schools. It’s really mandatory, I think, from an ethical perspective for us to say everybody had a fair shot and an equal opportunity there.”

For now, parents will get their lottery results in the coming weeks and decide whether the drive there is possible.

[Sign up for Alaska Public Media’s daily newsletter to get our top stories delivered to your inbox.]