In Alaska, 2022 was the year of the Independent. Freed by the state’s return to open primaries, nearly half of Alaska candidates running for governor, lieutenant governor, US House, and US Senate chose not to identify with either major party. As a result, the pool of candidates in those statewide races actually came close to mirroring Alaska’s majority-Independent electorate.

This and other changes may be the result of a decision by Alaska voters in 2020 to adopt a new election system pairing open primaries with ranked choice general elections. While many factors affect a candidate’s choice to run for office, we hypothesize the new system opened the door to candidates who wouldn’t have chosen to run otherwise, leading to a more diverse candidate cohort and more competitive races.

Sightline analyzed seven primary election candidate pools from 2010 to 2022. The focus was on statewide candidates. (Our analysis of state legislative races is coming in a separate article.) We found the 2022 statewide candidate cohorts looked different from earlier cycles’ pools in the following ways:

- More candidates identified as Independent and third-party.

- More Alaskans ran for office overall.

- No statewide primaries involved just one candidate (so, more of these races were actually competitive).

- More women ran for office.

Candidates drifted from the major parties

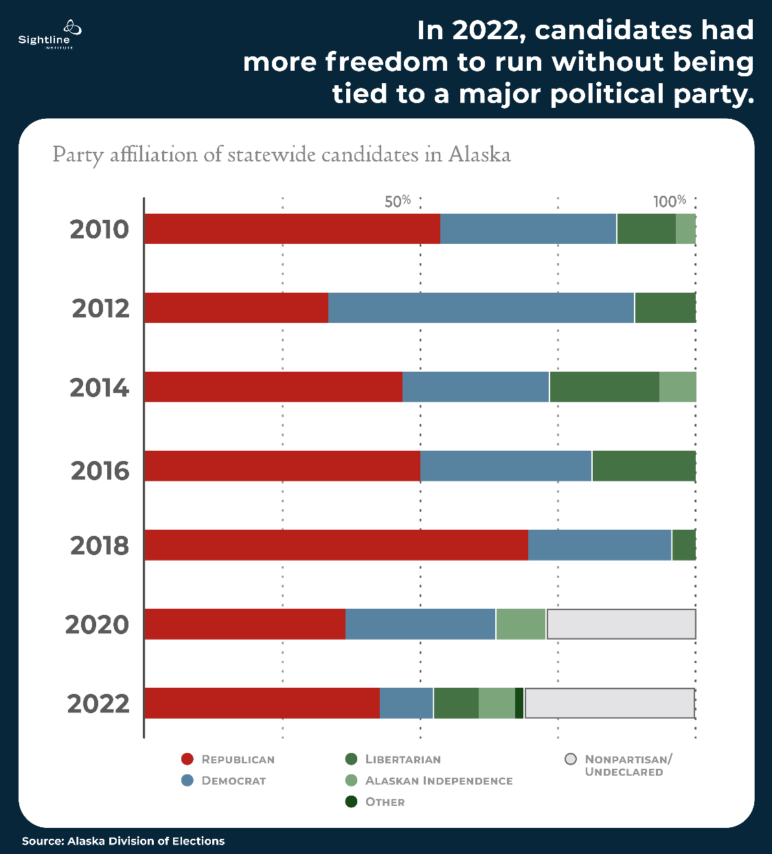

In 2022, the primary candidate pool came closer than ever to reflecting the independence of Alaska voters. About 58 percent of Alaskans are registered Independents, not affiliated with any political party, and another 5 percent align with third parties or political groups. But historically, candidates in Alaska have had far less freedom than voters to define their political identities.

In 2018, Jason Grenn, an Independent, was aiming for his second straight term in the state House. Grenn was one of just a few Independent candidates running, which was odd given that more than half of Alaska voters were Independents, too. The demand was there, but the supply was not. What could explain the disconnect?

Getting through an election is difficult for any candidate, but Alaska statute at the time put up particularly high barriers for candidates who didn’t identify as Democrat or Republican. Getting on the primary ballot required candidates to, well, run in a primary. And there were just two choices: the Republican primary or the Democratic primary. But you couldn’t just hop into a primary and run as an Independent. State statute required all candidates to register as a voter with the political parties running the primary they wanted to enter. On the Republican side, only Republicans could run. The Democrats had a slightly bigger tent, sharing their primary with registered Libertarians and Alaskan Independence Party candidates. (Note: The Alaska Independence Party is different from the “Independents” described in this article. Its primary goal is to hold a statewide vote for secession.)

“The party system locks people in in various ways from a candidate standpoint, where they can’t be themselves or vote for things because of the closed primary system.”

–Jason Grenn, former Independent candidate for the Alaska state House

Grenn had been a registered Republican, but as a fiscal conservative with progressive social views, running as an Independent felt more authentic. As a political hybrid, he had no natural home in the primaries. The only path was to get his name on the general election ballot through a petition process. And so, just as he had in 2016, he waited outside coffee shops and went door to door gathering enough signatures from registered voters in his district to get into the general. Grenn ultimately lost the three-way race, his old seat going to a Republican with less than half the vote. He now represents Alaskans for Better Elections, the nonpartisan group that led advocacy for Alaska’s new election system.

“I could honestly say I had conservative street cred, but I wanted to be more honest about who I was as a candidate and where my values were,” Grenn said in an interview this month. “The party system locks people in in various ways from a candidate standpoint, where they can’t be themselves or vote for things because of the closed primary system.”

After years of not appearing in primaries, Independents in 2020 accounted for more than a quarter of statewide primary candidates. The sudden increase occurred two years before Alaska’s election reforms took effect. What happened? In 2018, the Alaska Democratic Party changed its bylaws to allow Independents to run in its party primaries without having to register as Democrats, winning a lawsuit brought by the state Division of Elections in the process.

In 2022, the state’s new open primary system allowed primary candidates in both the special and regular elections to more easily opt out of the Democrat and Republican brands, and 48 percent of the 61 candidates did. Independent candidates made up 31 percent of the pool, their largest showing in the election years we analyzed. Interestingly, the share of Democratic candidates decreased to the lowest level in the seven-election sample. The shares of third-party and Republican candidates appeared unremarkable compared to previous years.

In 2022, Alaska’s new open primary system allowed primary candidates in both the special and regular elections to more easily opt out of the Democrat and Republican brands, and 48% of the 61 candidates did.

The marked decrease in primary dominance by major parties fell dramatically in 2020 as a result of the Democratic Party allowing Independents to run in its primary. The election reforms appear to have had an even greater effect on Alaska’s statewide primaries, with the 2022 share of major party candidates dropping by another 11 percent. Unlike past races, all candidates in each primary race jumped through the same hoops to get on the ballot, rather than major party candidates receiving preferential treatment. Candidates were free to self-identify as a registered voter with a party. But, as the ballot disclaimer stated, this did not imply that the party approved of or associated with the candidate. Like online dating, even if a candidate swiped right on a party, the party could swipe left or not respond.

The share of Independent candidates came closer than any recent election to mirroring the Alaska electorate’s majority-Independent composition. Greater political diversity in the candidate pool, especially with Independents, helped increase the chances that Alaska voters would find candidates who matched their political values.

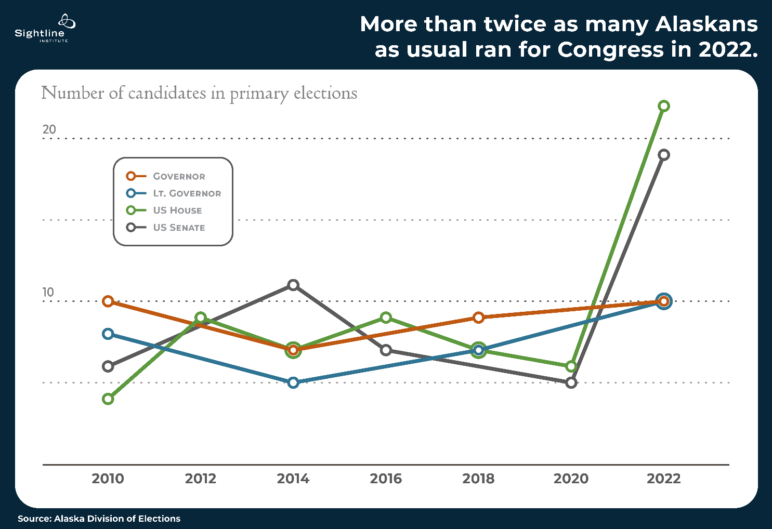

More candidates ran for statewide office

The number of candidates running in statewide races increased across the board to its highest level in the time period we examined. But while the races for governor and lieutenant governor only saw a slight uptick, interest in running for both Congressional seats spiked dramatically. In previous years, it was rare for more than ten candidates to run for any statewide seat. In 2022, the races for US House and US Senate saw more than double the usual number of participants.

For Santa Claus, a North Pole resident, the relative ease of entering the open primary and ability to coast on name recognition without doing any fundraising was a draw to entering the special election to serve out the term of Representative Don Young, who died in March. Young served in the US House for 49 years. (Note: Claus did not run in the regular primary.)

“In the old system, I would not have run because the major parties had it pretty much tied up,” Claus said. “I didn’t want to have to do the whole thing with the money and the staff and the paperwork.”

The novelty of the system may have encouraged more candidates to run. And Young’s death removed the incumbency advantage, possibly convincing more candidates to try their luck. Future elections will give us a clearer picture of whether Alaska’s open primaries and ranked choice general election mean voters here can expect larger candidate fields as a matter of course. (Note: Our analysis focused on Alaska’s regular primary races and did not include the special primary election for US House, which had a record-high 48 candidates on the ballot.)

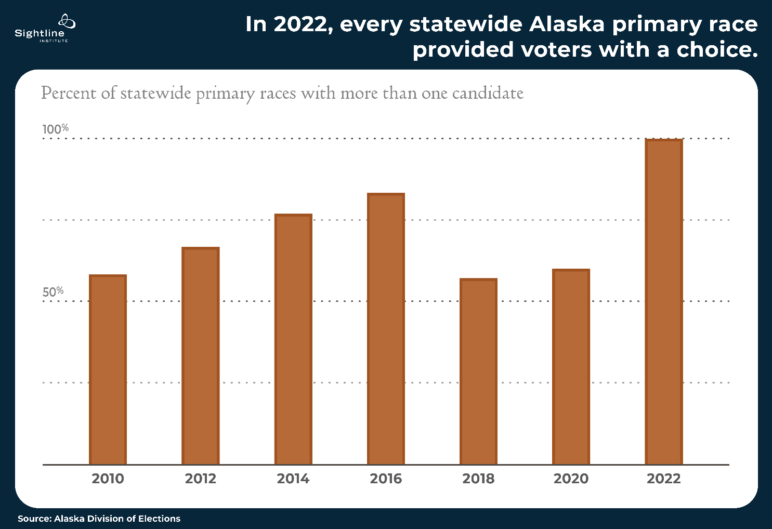

Alaska’s statewide primaries were more competitive

Before 2022, uncompetitive primaries were not unusual. Under the previous system, a candidate without an opponent essentially had a free pass onto the general election ballot. Voters in those cases had no choice about who to send to the general election.

In statewide primary races held from 2010–2020, almost every Democratic and Republican nomination included more than one candidate (28 of 32).1 In the case of third parties, specifically the Alaskan Independence Party and Libertarian primary contests, uncompetitive statewide races were the norm (11 of 14).2

With the adoption of open primaries, the statewide primary contests became exceedingly competitive. No statewide primary in 2022 had fewer than 10 candidates, as shown in the figure above, meaning voters had more choice than before the election reforms took effect.

Alaska didn’t always have closed primaries. In 1947, a dozen years before statehood, Alaska voters approved a blanket primary that listed all candidates on a single ballot, regardless of party, and the top vote-getter from each party advanced to the general election. Since then, legislative actions and lawsuits brought by political parties have changed up the primary format numerous times. In the six statewide primary elections we analyzed before 2022, the Republican party opted for a closed primary format, where only Republican candidates could appear on the Republican primary ballot. The Democrats had a combined blanket primary with third parties in that period.

The inclusion of Independents on the Democratic ballot, starting in 2020, may have boosted Independent participation in statewide primaries, as noted above, but did little to improve competition. For instance, in 2020, Senator Dan Sullivan ran unopposed in the Republican primary, winning 100 percent of the vote. Another non-major party candidate that year made the general as the top vote-getter in their party despite only winning a sliver of the vote. Only the return of the open primary in 2022 brought true competition back across all races: as shown in the figure below, every single statewide primary was competitive.

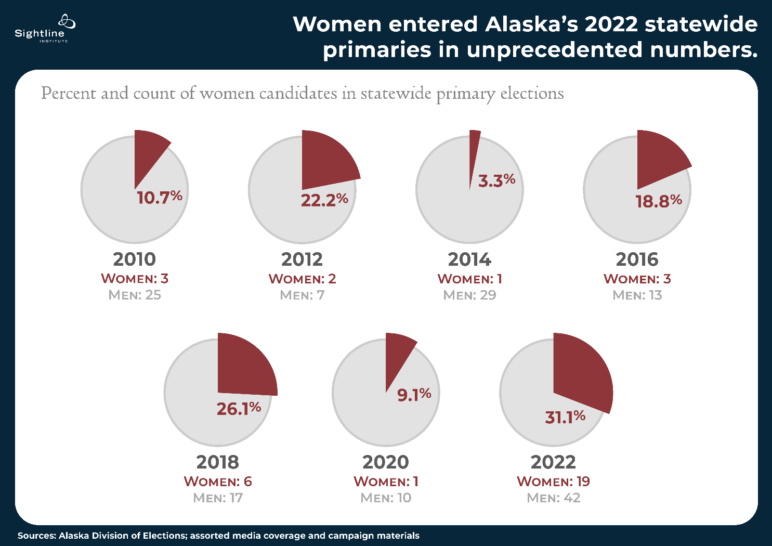

More women ran in Alaska’s 2022 primaries

Former governor Sarah Palin, Senator Lisa Murkowski, and Representative Mary Peltola: in a state with a reputation for a high ratio of men to women, women are headlining this election cycle.

They’re not outliers, either. In 2022, nearly one-third of statewide primary candidates were women, the highest rate in the years we examined. Research by the nonprofit RepresentWomen, which advocates for reforms that improve gender parity in politics, suggests ranked choice elections can help. A RepresentWomen study posited that ranked choice voting makes elections more women-friendly by reducing concerns over vote splitting between women candidates, incentivizing more cooperation between candidates, and lowering the financial barriers for all candidates.

But how much the new system affected the decisions of women candidates in Alaska to run is hard to say at this point. The participation of women in Alaska’s statewide primaries has been erratic since 2010, seesawing between double- and single-digit percentages, as shown in the figure above. This cycle, women may also have been motivated to run by the US Supreme Court’s leaked decision to overturn the federal constitutional right to abortion. And nationwide, more women have moved into powerful political roles in non-ranked choice elections. The number of women in Congress is at a historic high, according to a report in October by the Congressional Research Service. And women have made political gains elsewhere: the vice presidency, the president’s cabinet, governorships, mayor’s offices, and city councils.

Political strategy around the lieutenant governor’s position may be a key reason the percentage of women in Alaska’s statewide races is so high. Before 2022, candidates for governor and lieutenant governor ran in separate primary races. The winners of each would appear as a single ticket on the general election ballot. The election reforms in 2020 changed the law so that the governor and lieutenant governor ran as a single ticket starting in the primary. All ten primary candidates for governor were men, and eight of them tapped women to run as their lieutenant governors. This means Palin will continue her run as the only woman to have served as governor of Alaska.

At least one candidate for governor, Les Gara, had gender diversity in mind when he asked Jessica Cook to join him on the ticket.

“We’re regionally diverse, we’re ethnically diverse—those aren’t why I picked Jessica, but let me tell you, I would have had a little knot in my stomach if it was two white men from Anchorage running,” Gara told Alaska Public Media.

What about race?

We did not include information about racial diversity among statewide primary candidates because filings with the Division of Elections and media coverage did not include comprehensive information on race for all candidates.

What else?

Our analysis forms an early outline of the changes accompanying the debut of pick-one open primaries and ranked choice general elections in Alaska. We’re pretty sure the new election system had a nonzero effect on candidate demographics this year, but data from future elections and some post-election polling and interviews will help fill in the picture.

Our biggest questions looking forward: Will these trends hold? How much does Alaska’s election system affect candidates’ choices to run versus other factors? Can we expect the same dynamics in other states should they decide to replicate Alaska’s system?

So far, what we do know is encouraging: Voters in statewide races had more choices than ever, with a more politically diverse and gender-diverse pool of candidates, more competitive races, and more candidates to choose from overall.

Editor’s Note (11/10): Santa did not do ANY fundraising, so we have updated our article to reflect the correction.